4 minutes of occasional recordings of train sounds, constantly persistent underwater sounds over “The Pyre” by Body Sculptures.

Before you start reading, make sure to start the audio:

“People hear ringing, hissing, roaring, crickets, screeching, sirens, whooshing, static, pulsing, ocean waves, buzzing, clicking, dial tones, and even music.”

The above is an excerpt from a SoundRelief article on “tinnitus,” a condition where a person hears a sound, a ringing, a persistent presence of a frequency without an actual external stimuli creating it. It is considered to be more noticeable in a quiet room. Where no sound exists and nothing is there to make it.

My morning and afternoon commute in middle school consisted of me, a Nokia 6300, wired earphones, and a library of pirated .mp3s from a Russian music distribution site called zaycev.net. A library with hand input metadata for each file, always resembling the actual thing. With no sound isolation inside the repurposed trains, every song on the playlist would be layered over the squeal of the stainless steel rail and the rumbling of the train cars on each turn. The pattern of each rotation, pauses in between loud and subtle shakes, and the length of the squeals became a muscle memory. A noisy and scattered morse code, never existent on paper — only in the indifferent air.

The close knit touching of cold yet sparking train tracks travelled from the vacuum of the tunnel through the beige interior of the train car, onto the irregularly stained plastic floors, embossing itself onto the leather seats until it reached my ears. With this light but consistent magnitude, at the end of each trip, a sound would linger and accumulate. Not giving it a thought, I’d say that it was just because of listening to loud music, in my attempts to make the music more pronounced over the noise outside. Alas with no success, I would still try to wiggle my finger in my ear and try to get rid of it, to scoop out the remaining sound. The walk from the metro station to the school is a light uphill stroll. Unnoticeable at first but the pressure changes slightly, blocking both ears. A cotton of air starts taking up space, dangling from my left and right ear. In this castling of noise pieces, the lingering metro not fully yet slowly dies out, only to be restarted the following morning. The end of the walk and the beginning of class carries this after-image.

How could you take a sound and not give it back?

Looking it up online, there are various but indefinite names for the phenomena of an auditory after-image. Some researchers at the National Library of Medicine call it “auditory-after image and tonotopic response,” some people on r/edmproduction subreddit just call it an “auditory after-image.” The after-image, visually perceived, is described as an image that continues to appear in the eyes after a period of exposure to the original image. In its nature, it creates a gap between the original and the residue. Never close enough to replicate the original, but long enough to stay.

The visual kind has a lot of examples of illusions, inverted images with dots in the middle being the most common instance of it. 30 seconds to look, and 20 seconds to decay. Sound, however, doesn't have a clear distinction when it comes to the case of an after-hearing. It travels from one ear to another and does a loop until another sound replaces it. Even when the actual stimuli isn’t there, the sound can get plastered, nestles, fills the crevices of the ear's snail, refusing to leave: the rumbling of train tracks, a northern cardinal’s cry and a mother’s call.

I can’t grab it, I can’t hold onto it, I can’t record it, I can’t prove it in any way.

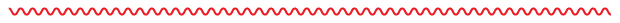

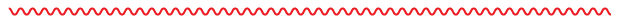

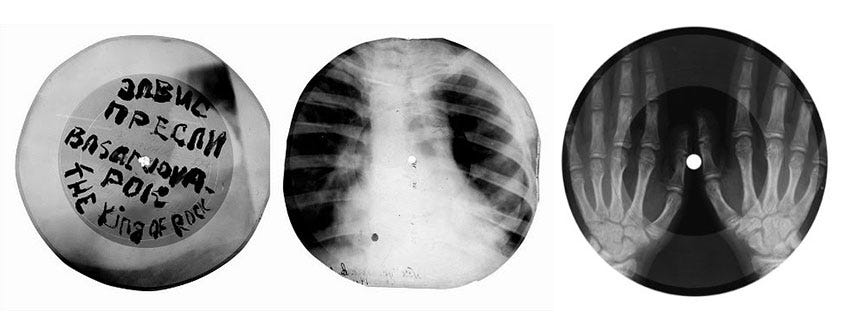

I can’t prove that body carries sound, except just to hear it. Before the Russian music piracy websites spread throughout the 2000s and 2010s, ribs were main vehicles for sound. Picked up from the trash of hospitals and clinics, X-Ray films of rib cages and chests would be turned into disks specifically within the speed of 78rpm. With a cigarette burn hole in the middle for the spindle and a deep lo-fi quality for the ear. It manifested itself as a way of listening to something that wasn’t supposed to be heard. Just as ephemeral in its creation, they could only be played five to seven times, after which the sound would lose its pace and vibration. After seven times, the needle of the gramophone would slowly start to eat out layers of thin film until the grooves are flattened and almost non-existent. A non-human contact disappears the sound, leaving the person to fill in the gaps and to create more sound from the bodies. The rot of an acoustic wave gets transmitted from the melted vinyl to chloride gas to the ear of its choice.

If you won’t give it back, how can I keep mine?

Between the state of falling asleep and actually sleeping, underneath my eyes there’s always an image of a car, specifically a black SUV growing and shrinking rapidly. Its hectic existence is accompanied by a whistling sound, changing its pitch according to the size of said car. A similar moment happens when I swim in a closed pool. The taste of chlorine enters my mouth, and a considerable amount of water comes out of my ears. The eustachian channel gets contaminated by chemicals, neutralizing smell and taste, leaving sound as the most active component. The only organ that keeps receiving. The clapping of a person’s two second butterfly stroke from another corner lives in the lobe for a moment. A slap to the water, reverbing through my temple. A glimpse of a shore within the confinement of blue and white ceramic tiles and colored lane dividers.

I try to record it, to measure this sound, to see whether it’s in my head or somewhere out there. Every single attempt is a reenactment of a wet choreography. I won’t only hear it once. Each time it will take a different dying volume. So I let it rest, until I hear it again.

Rasim Bayramov is a designer from Baku who through their work is trying to fill in the gaps with slowness still enough to keep us both here, long enough to stitch the rubber of our shoes to each other.