This is the first transmission of Bad Sense, a newsletter from a grad seminar led by Meg Miller at VCU’s School of the Arts in Spring 2025. Below is Meg’s attempt to give some context to the course and by extension, the writings that come out of it. But for some quicker context: anyone who signs up will receive a newsletter every Sunday authored by one of the 13 participants in the seminar. Each piece will be a response to one of the prompts or assignments given in class, and so will have something to do with our main obsessions: translation and the senses. Each week will be different, a surprise, a little gift to your inbox, and then, after 15 weeks (the duration of the semester) it’ll be over. After that, we’re thinking we may archive our writings in a website or a book, or both. Let’s see.

In October, Nicole asked me if I would teach the grad seminar in the spring. They texted we should connect! was thinking about you for the grad seminar this spring. I suggested we meet for lunch, but they had to cancel because of a last-minute meeting. Phone call? I texted. yes! They texted back.

I was coming back home from the corner store when they called, walking down my block under the changing fall leaves, lush bursts of deep red and burnt orange above, dried ashes of brown crunching under foot. After we talked Nicole asked if I had an idea yet for the class, but I didn’t so I told them I would think it over.

Later while sitting with Kai on our roof, watching the sun drop slowly below a horizon line jagged with chimneys, I pitched him on two still-forming ideas. Either way, the seminar would be about writing, but should it be about interviewing, as a form of writing, or translation, as a framing for writing? Kai listened with his eyes closed, his head resting on the back wall of our apartment building. I think you should do it on translation, he said.

I am not a translator. I speak two languages, but just barely. I like literary works in translation, and I have an enduring fascination with sociolinguistics, but neither of those qualifies me to teach a course on literary or linguistic translation. Instead, when I said translation, I was thinking something more like this:

Increasingly I have felt that the art of writing is itself translating, or more like translating than it is like anything else. What is the other text, the original? I have no answer. I suppose it is the source, the deep sea where ideas swim, and one catches them in nets of words and swings them shining into the boat…

—Ursula K. Le Guin, “Reciprocity of Prose and Poetry”

Le Guin positions all writing as a form of translation, and the thing being translated as (possibly) ideas, experiences, feelings, memories, sensations. Like literary translation, writing is the act of creating something new, but unlike literary translation, there is no original text to work from. Or maybe there is but you are translating from “a text that is not words, and you find the words.” Later in the essay, Le Guin writes,

I want to learn how to make translations from the languages nobody knows, nobody speaks. The translations will not be as good as the originals, but then, they never are.

This, I thought, would be the starting point for the class. We would be translators of the non-verbal — the non-textual — into written language. Since I am an art and design writer, and this seminar would be with art and design students, perhaps we could think specifically about art writing as a form of translation, a carrying over from the visual to the page.

The words we bring to art intend, at best, to translate the perceptual realm into the linguistic, anchoring sensation through definition.

— Charlotte Kent in The Brooklyn Rail

And while we were bringing things into the linguistic realm from perceptual realms, why not translate scent as well? Despite being so tied to memory and nostalgia, fragrance is notoriously hard to describe with words. Scent is arguably a language that nobody speaks. All the better to create something new with it.

And then there was sound, touch, taste… all ripe for translation. I felt I was getting somewhere.

Nicole said they just needed a short description of the class, two sentences max, which they could send around to the various departments. I opened up my Notes app in the waiting room at the dentist. In the corner was a large spider web made of cotton balls stretched to near-translucency. Below it was a black gauze-y witch with no face that nevertheless seemed to be looking at me. The young assistants were all chatting around the desk of the receptionist, who was playing Clairo.

Created: 20. October 2024 at 09:01

Idea for seminar

Art writing translates perception and sensation into language. Moving across media and the senses could also be considered a translation: Graphic notation visualizes sound; architectural notation turns space into symbols. Fragrance reviews describe scent with words. In a way, all writing and art-making is an act of translation, an approximation of the thing. In this seminar, we’ll look at work that manifests in many different forms and consider what’s gained and what’s lost in translation.

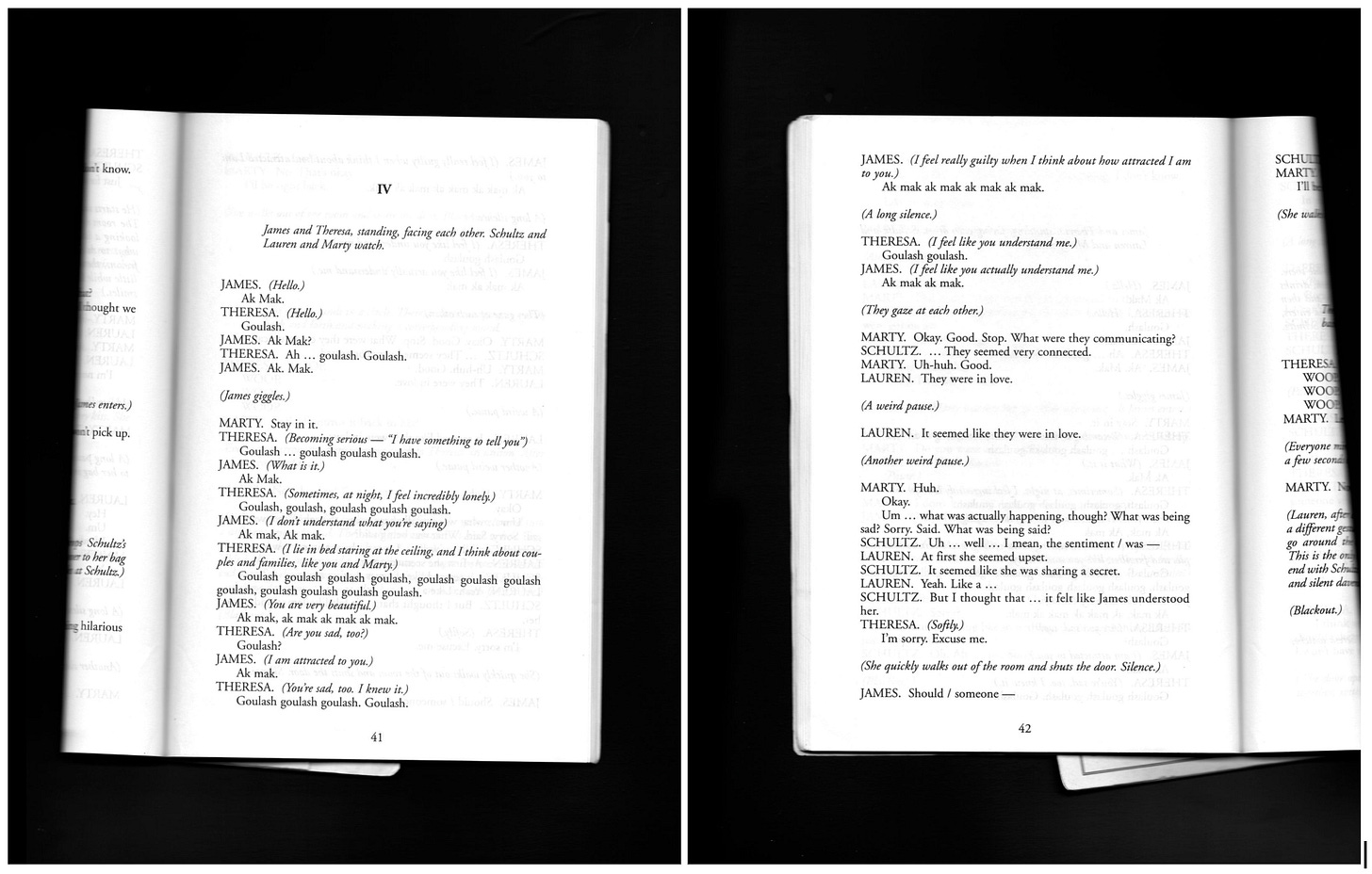

Back at home, I texted the description to Luiza to see what she thought. at this point it’s a lot of air I cautioned. She texted back translation is huge!! Then she sent me photos of pages in an Annie Baker play called Circle Mirror Transformation, in which two people are doing an acting exercise in front of three other people.

The pair stands facing each other. They try to hold a conversation, each speaking a private language they made up:

Reading this made me feel both hollow and full. Outside my window, the tree branches were getting more and more bare and the wind was whistling through them. I put my phone down.

It lit up with another message from Luiza. I think it's about exploring how, no matter what is said/if we can understand the language or not, there is a message that is being sent/received. We share/make meaning all the time and language is just one component of things.

In January, back from break, I returned to my Notes-app description with the intent to spin it into a full syllabus. Outside, the sky was the shade of white that makes the world fall silent. Richmond had been hit by an arctic blast, which meant a few inches of snow on the ground and the city at a standstill, even before a power cut at the pump shut off everyone’s water for a week. I had rosemary focaccia in the oven, and the heat hitting the fat of the oil enveloped the room in a smell that was deep and rich and warm. I sat at my kitchen table with a pile of library books and pecked out my reading list.

Translation is amazing, because it presumes there is something that needs to be carried from one place to another. But where is that thing?

— Renee Gladman, “The Sentence as a Space for Living”

I titled the seminar Sense-to-Sense Translation: Writing Images, Sound, and Scent and hoped it made sense. I was going for a play on the term “sense-for-sense translation,” an approach to translation that prioritizes the overall meaning of the text over a literal translation of each exact word (word-for-word translation). In this way, our translations (writings) would attempt to carry over the soul of the source, the original — an artwork, an experience, a memory, whatever it may be. Sometimes our sources would be music, sound, scent, taste — those experiences that push up against the limits of language, requiring a whole new use of it — and so in another way, we would also be translating across the senses, from sense to sense.

I asked Laurel to look over my syllabus. On the phone afterwards she said that this theme of translation articulates a lot of what she loves about art. She said, Artists are sensitive and that’s what makes them good receivers and translators of material, the essence or spirit of things.

Laurel recommended Sawako Nakayasu’s book-length poem Say Translation Is Art, and we read it out loud on the second day of class, going around the big table in the grad studio and each reading a part until the poem was finished. Say Translation Is Art is a beautiful list of demands. It starts:

Say this

Say not this

Say it again

Like this

It’s choral, polyvocal:

Say Pauline Oliveros’s Sonic Meditations translation.

Say James Turrell’s light into physical material translation.

It’s repetitive and expansive — big enough to hold all the ways we could think about translation in this class, open enough to allow for our own additions:

Say “bad” translation

Say “F” translation

Say ephemeral translation.

Say misfit, unpopular, unloved translation

Now it’s February, it’s warm one day and biting cold the next, every jacket of any thickness is out, weighing down the coat rack. We’re three classes in and each time we meet the others enrich and challenge and complicate the way that I’m thinking about translation, this framing for art, writing, and art writing.

Each week we write something, sometimes on scent or sound or visual art. Sometimes on mythology, sometimes on the myth of the original and the copy, or on the myth of a “correct” translation. Like translators, we are paying close attention to word choice and rhythm, meter, measure, cadence, tone. Like artists we are trying to be sensitive to the world, we are sharpening our observational acuity, attuning our senses, and recognizing that art-making is an act of faith (Tyna). We are accepting that language can only be an approximation of the thing, and we’re embracing that ambiguity.

We are also learning this: that meaning shifts with context. That sometimes language fails us, or stops itself or stutters; is scarred or silenced or broken with grief. Sometimes it doesn’t account for other ways of knowing (Diego Pablo), or is the language of oppression, and is impossible to speak. And sometimes we just have to work with the material we have, but there are no rules on how we use it.

Language is not merely a tool for communication. It often hides rather than articulates, holding between its silence endless possibilities not concerned with expression. Language can be attacked, abused.

— Adania Shibli in the Guardian

We are learning as we go. If translation is the lens we’re using to think about, talk about, and do writing within an art practice, then every class feels like a turn and click of the refractor, an increase in clarity. Over the course of the semester, things will continue to slide into focus.

We’d like to invite you to follow along, through weekly writings published in the form of a newsletter. None of these writings are exact copies of an original, none correct or accurate or polished or final. All are new, all approximations, all still works in progress. All are bad.

Does that make sense?

This post features (in order of appearance): Nicole Killian, Luiza Dale, Laurel Schwulst, Tyna Ontko, and Diego Pablo Thank you <3

Meg Miller is a writer and editor in Richmond, VA. This semester she’s teaching Sense-to-Sense, a writing seminar at VCU’s School of the Arts.